Leadership is not defined by title or authority. Leadership is defined by influence.

Every leader, regardless of role or seniority, shapes outcomes through the way they exercise influence, what they prioritise, how they apply pressure, how they respond to challenge, and how they behave when the stakes rise. The ethical quality of leadership is therefore inseparable from the quality of leadership influence being exercised.

they prioritise, how they apply pressure, how they respond to challenge, and how they behave when the stakes rise. The ethical quality of leadership is therefore inseparable from the quality of leadership influence being exercised.

Ethical leadership does not fail because leaders lack values. It fails because leadership behaviour drifts under pressure.

Every leader, regardless of role or seniority, shapes outcomes through the way they influence others, what they prioritise, how they apply pressure, how they respond to challenge, and how they behave when the stakes rise. The ethical quality of leadership is therefore inseparable from the quality of influence exercised.

Ethical leadership does not fail because leaders lack values. It fails because behaviour drifts under pressure.

Leadership as an Influence Process

Leadership scholars have long defined leadership as a process of influence rather than a function of position (Northouse, 2021; Yukl, 2013). Authority may secure compliance, but leadership influence determines whether people engage honestly, take responsibility, and apply judgement, particularly in complex or high-pressure environments.

This matters because leadership influence is rarely neutral. It can enable learning and trust, or suppress challenge and create silence. The same leader can generate very different outcomes depending on how they regulate their behaviour, particularly under stress.

How Influence Becomes Ethical, or Not

Influence operates through three interacting elements:

-

Power base: where influence comes from (role, expertise, relationships, information).

-

Influence tactics: what the leader does (persuasion, consultation, pressure, framing).

-

Intent: why the leader is influencing and whose interests are being served.

Research on power and influence shows that tactics such as rational persuasion and consultation are more likely to generate commitment, while pressure-based tactics tend to produce compliance and resistance (Yukl & Tracey, 1992). However, effectiveness alone does not make influence ethical.

Ethical leadership is defined by transparent intent, respect for autonomy, and regard for others, even when outcomes are uncertain or inconvenient (Brown, Treviño, & Harrison, 2005).

This is where leadership becomes vulnerable, not to incompetence, but to drift.

Behavioural Drift Under Pressure

Behavioural drift occurs when leaders gradually move away from their stated values without consciously choosing to do so. Under pressure, urgency narrows attention, emotional regulation weakens, and leadership influence can become more controlling, more selective, or more coercive.

Drift is rarely dramatic. It often sounds like:

-

“We don’t have time for debate.”

-

“They don’t need the full picture.”

-

“I’ll explain later, just get it done.”

Over time, these micro-choices shape culture. Influence shifts from enabling judgement to extracting compliance.

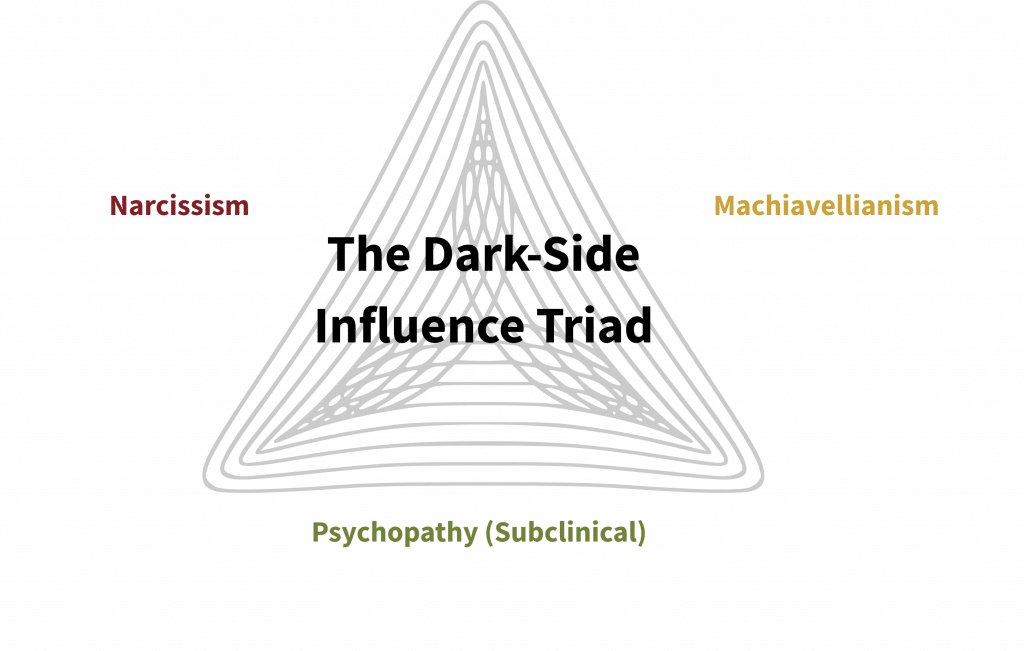

The Dark Triad and Risky Influence Patterns

Research on the Dark Triad, narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy, helps explain why leadership influence can sometimes appear effective while simultaneously undermining trust and ethics (Paulhus & Williams, 2002).

This discussion refers to behavioural patterns under pressure, not personality labels or clinical diagnoses.

-

Narcissism is associated with entitlement, overconfidence, and sensitivity to ego threat.

-

Machiavellianism involves strategic manipulation, emotional detachment, and instrumental use of others.

-

Psychopathy is characterised by low empathy, impulsivity, and reduced concern for consequences.

Importantly, dark-side influence does not require clinical traits. Under pressure, even well-intentioned leaders can temporarily adopt dark-side behaviours, becoming more controlling, more strategic, or more emotionally detached (Babiak & Hare, 2006).

The ethical risk lies not in labelling leaders, but in failing to monitor behavioural signals of drift.

Concepts such as the Dark Triad are not used here as diagnostic labels or character judgements; rather, they describe recognisable patterns of behaviour that can emerge in anyone under pressure, threat, or unchecked power.

Ethical leadership therefore depends less on who a leader is and more on whether they can notice these shifts early, regulate their behaviour, and recalibrate their influence before short-term effectiveness erodes trust, information flow, and long-term performance.

Dark-side influence is rarely about bad people.

It’s about unregulated behaviour under pressure.

Leadership maturity shows up in how quickly influence is noticed, interrupted, and redirected.

Trust, Psychological Safety, and Influence Risk

Influence is mediated by trust. People assess both a leader’s competence and their motives before they speak up or take interpersonal risk. Research shows trust in leadership is strongly associated with performance, engagement, and cooperation (Dirks & Ferrin, 2002).

Psychological safety makes trust actionable. Edmondson (1999) defines it as a shared belief that it is safe to speak up, ask questions, and admit mistakes. When leaders rely on pressure, fear, or selective transparency, psychological safety deteriorates, even if performance targets are met.

For Senior Leadership Teams, this creates a practical reality: pressure-based influence may accelerate decisions, but it simultaneously reduces the quality of information leaders receive.

Behavioural Intelligence: The Safeguard Against Unethical Leadership Influence

Behavioural intelligence is the capacity to translate insight into observable, regulated behaviour, especially when emotions, risk, or power are in play. Four behavioural capabilities are critical to ethical influence:

-

Emotional Regulation: managing urgency, frustration, and threat responses rather than transmitting them as pressure (Gross, 1998).

-

Social Awareness and Regard for Others: recognising power asymmetry and reducing the interpersonal cost of dissent (Goleman, 1998).

-

Assertiveness with accountability: holding clear boundaries while remaining open to challenge and dialogue.

-

Purpose-anchored influence: framing work around meaning and shared intent, supporting autonomy rather than compliance (Ryan & Deci, 2000).

Behavioural integrity, the alignment between what leaders say and what they do, is the consistency test. When words and actions diverge, influence erodes rapidly (Simons, 2002).

Ethical Leadership Versus Manipulation

Ethical leadership and manipulation can look similar on the surface. Both may be decisive, persuasive, and effective in the short term. The difference lies in choice and transparency.

Ethical influence expands others’ capacity to think, choose, and contribute. Manipulation narrows it. While manipulation can deliver short-term gains, it corrodes trust, capability, and long-term performance (Brown & Treviño, 2006).

A practical leadership check is simple:

-

Would I stand by this influence if it were fully visible?

-

Am I enabling informed choice or engineering compliance?

-

If this decision fails, would I still defend how I influenced others?

Leadership is exercised through influence long before it is recognised through outcomes.

Ethical leadership is not about perfection or moral superiority. It is about behavioural awareness, regulation, and correction, especially when pressure makes drift likely.

When leaders build behavioural intelligence and actively monitor their leadership influence, leadership shifts from control to credibility, from pressure to purpose, and from short-term results to sustainable trust.

That is the quiet discipline of ethical leadership.

flowprofiler®’s Leadershipflow® pathways go beyond competency frameworks by making leaders’ influence patterns under pressure visible and measurable. By identifying early signs of behavioural drift across Emotional Regulation, influence style and Regard for Others, Leadershipflow® enables timely intervention, protecting ethical leadership, trust and information flow before damage occurs.

Reach out to us at hello@flowprofiler.com to find how we can develop behavioural intelligences that drive outcomes in your leaders.

References (APA 7th)

Babiak, P., & Hare, R. D. (2006). Snakes in suits: When psychopaths go to work. HarperCollins.

Brown, M. E., Treviño, L. K., & Harrison, D. A. (2005). Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97(2), 117–134.

Brown, M. E., & Treviño, L. K. (2006). Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(6), 595–616.

Dirks, K. T., & Ferrin, D. L. (2002). Trust in leadership: Meta-analytic findings and implications for research and practice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), 611–628.

Edmondson, A. C. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383. Goleman, D. (1998). What makes a leader? Harvard Business Review, 76(6), 93–102.

Gross, J. J. (1998). The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Review of General Psychology, 2(3), 271–299.

Northouse, P. G. (2021). Leadership: Theory and practice (9th ed.). Sage.

Paulhus, D. L., & Williams, K. M. (2002). The Dark Triad of personality: Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy. Journal of Research in Personality, 36(6), 556–563. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(02)00505-6

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 54–67.

Simons, T. L. (2002). Behavioral integrity: The perceived alignment between managers’ words and deeds. Organization Science, 13(1), 18–35.

Yukl, G. (2013). Leadership in organizations (8th ed.). Pearson.

Yukl, G., & Tracey, J. B. (1992). Consequences of influence tactics used with subordinates, peers, and the boss. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77(4), 525–535.